Vasarely, the magician

The ambitious exhibition in Centre Pompidou, Vasarely: Le partage des forms (Vasarely – Sharing forms) aims to provide an overview of the artist’s oeuvre, from its early, avant-guard inspirations to the industrialised op-art. The idea might seem old-school, but in the case of an artist like Vasarely, it might still be too multi-faceted.

The first room, introducing the early years of Vasarely, is not only interesting from a subjective (or even patriotic) point of view, as the op-art masterpieces often overshadow the early works inspired by the avant-guard constructivist trends, especially by Bauhaus. There were other important influences as well: for example, the intellectual milieu of the Műhely in Budapest, and the works of Vasarely’s master, Sándor Bortnyik. Two of his paintings are exhibited, The New Adam and The New Eve (1924). Both paintings are engaging works of art, that should be interpreted in the context of Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus-dolls and ballet-dancers, but they are reduced to dolls and robots – Kleist seemingly predicted them in his essay on marionette theatres; and Chirico’s surrealistic Neo-Mannerism. Vasarely’s L’homme is presented next to Bortnyik’s diptych; it is a perfect example for showing how Vasarely was prepared to take the next step: the figure of the marionette is more homogenous, while the space is no longer enclosed within the illusion of its own boundaries that the spectator stares into.

The figures, whose shapes strip them from any individuality, completely transform the space, render it dynamic, the central character (humanity itself?) is represented running towards the spectator, and the spatial dynamics is enforced by the frozen movements of the accessory figures.

While earlier artists focussed on space, Vasarely aimed for providing a frame frozen in time, and thus the painting requires a different reception mechanism: the spectator no longer projects themselves into the spatial dimensions of the image; the space is aware of the spectator and it projects itself upon them, and this illusion provokes the audience to react: either to jump out of the way or to run along with the figures. This trait is a deliberate first sign of the illusivity of op-art.

The exhibited newspaper cover pages – by courtesy of the Vasarely collection of the Hungarian Museum of Fine Arts – also illustrate the flourishing intellectual life in and around Bortnyik’s school, during the 1920s and 30s. The cover page of Almanach (by the renowned publishing house, Athenaeum) from 1930 might be misleading, as a literary anthology hides behind the aesthetic cover. The exhibition includes a few copies of the magazines Het Overzicht and Ma (Today) – the copies of the latter include the manifestos from Herwarth Waldean (on technology and art) and Theo van Doesburg, the founder of De Stijl (From the New Aesthetic to its Material Realization), written under the influence of the Walter Gropius-led school of Bauhaus in Weimar. From the perspective of the exhibition, however, Kassák’s Constructivist, geometric illustrations are more important. Claire Vasarely’s cover arts for Athenaeum and French publications – by courtesy of the Janus Pannonius Museum in Pécs – from the 1930s are also astonishingly stylish.

Of course, there are illustrations from Victor Vasarely as well since after his move to Paris he worked as a graphic designer for quite a long time. The works of this era can be seen as creative attempts to adapt the symbolism of Modernism to the challenges of the mass communication-bound advertisements, an important step towards a more mature period.

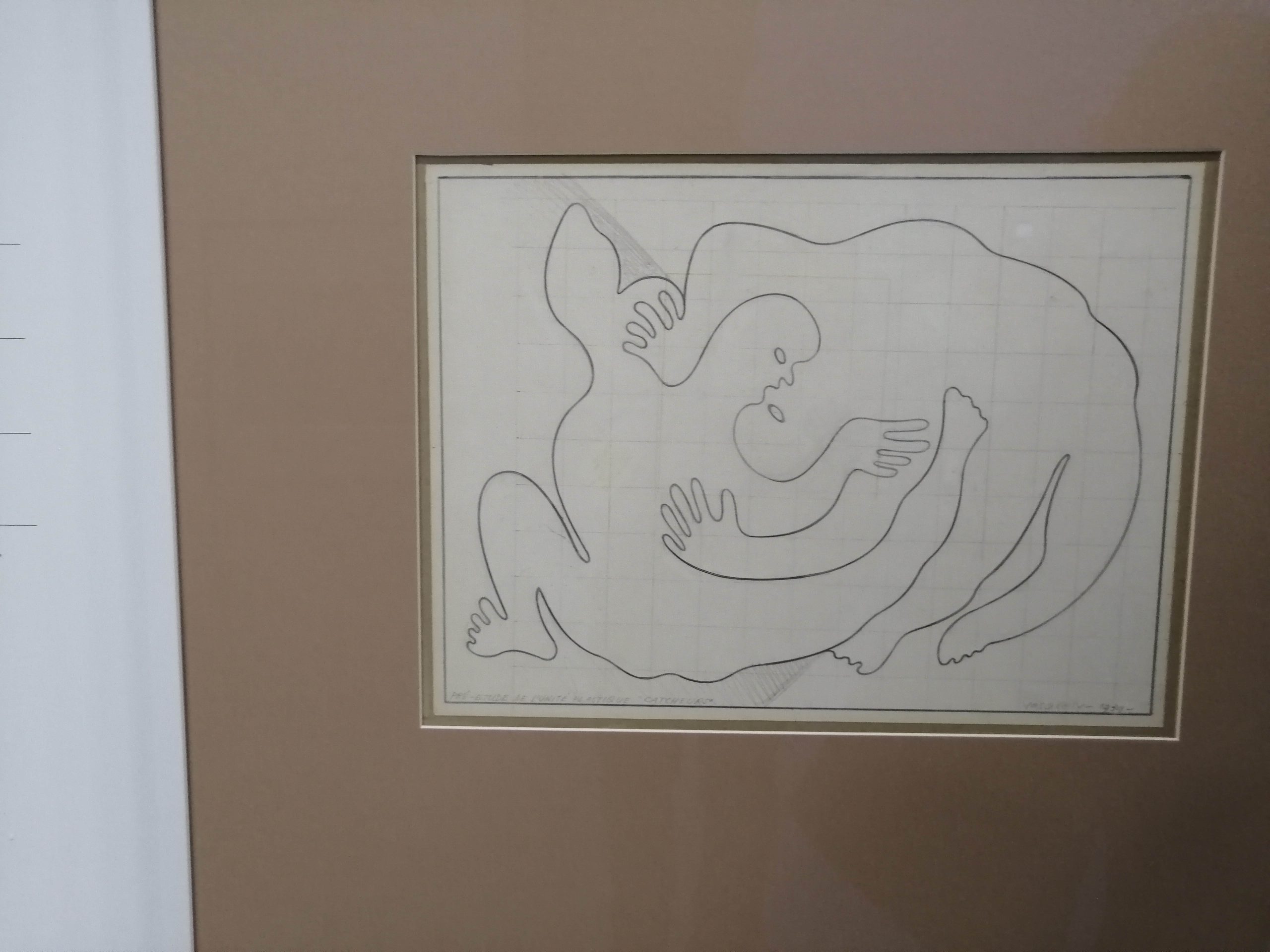

The emblematic Zebra cycle is a clear proof of how he moved from the Constructivist traditions towards playful optical illusions; however, there are other works where a twofold, yin-yang contrast is observable (e.g., Catch, 1939; Amor, 1945; Les Lutteurs, 1944), while Étude de movement (1939) shows a beautiful transition from the figurative to the abstract optical illusions as the whale coming up for air is surrounded by concentric water ripples.

Paintings from the Aix-en-Provence collection – donated by Vasarely himself to Alexandre Dauvillier and Werner Heisenberg – manifest a different, exciting experimental direction. The artist became an avid reader of scientific publications in the 1930s-1940s, and the donated collages use the micrography technology created by Laure Albin Guillot, which, by that time, had already caught the attention of many artists. Behind the enlarged structure of cells and crystals, Vasarely started to analyse the inner geometry of nature.

The 1950s were dominated by compositions of shapes and colours. The many shapes of the rocks in Bretagne inspired the elliptic compositions of the Belles-Isles cycle (e.g., Kreisle, 1949). The scientific interests were also supplemented by a hint of Cubism, stimulated by the sunlit roofs, forms and horizons of Gordes, a small town in the south of France, as Vasarely bought a cottage in the town, and the castle has an impressive collection of the artist’s works.

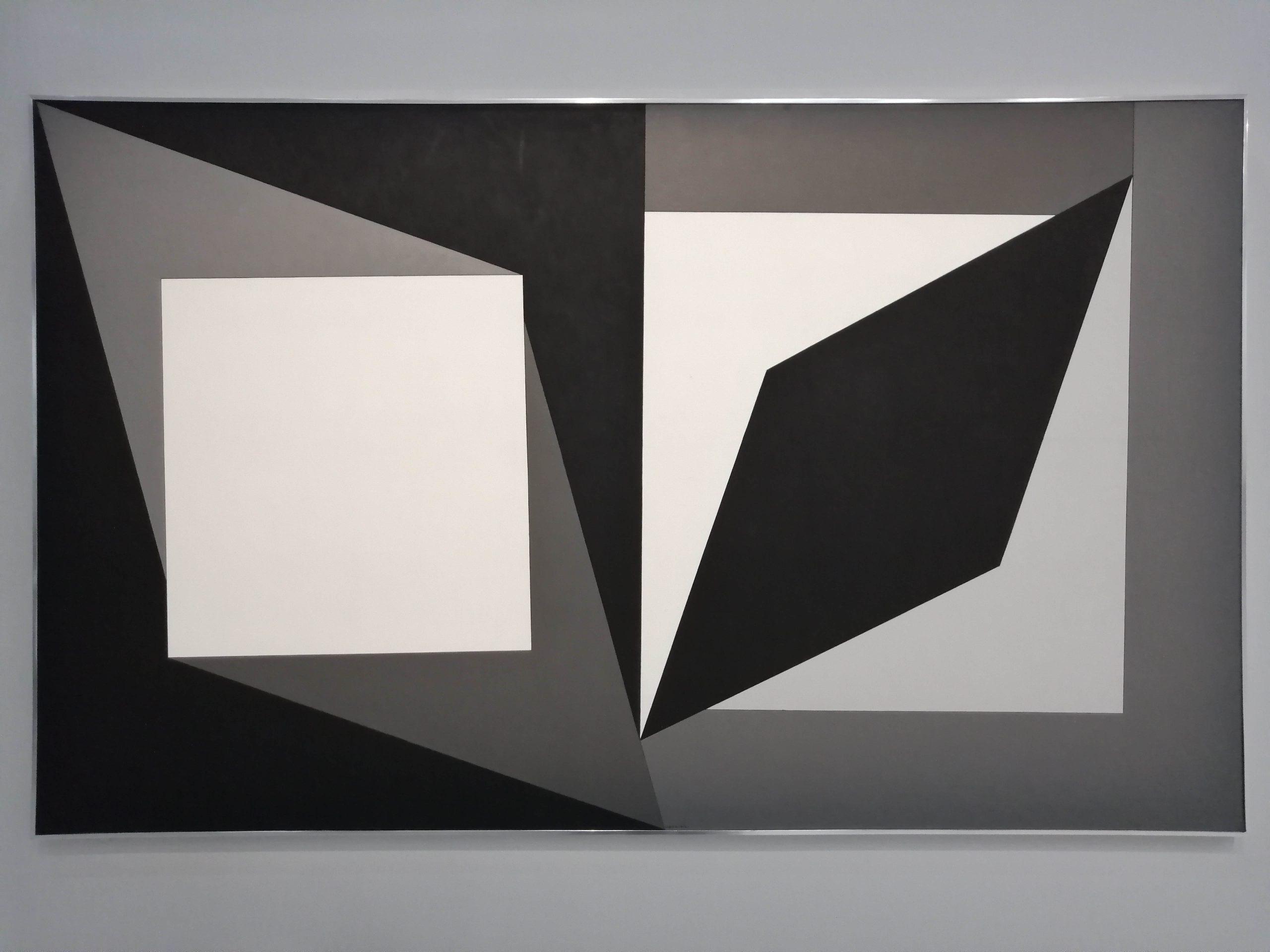

It seems that spectators now are mostly interested in the coldly geometric paintings from this period. The sheer geometric, black-and-white painting not only suggest the influence of Malevich, but paintings like Hommage à Malévitch undisputedly pay tribute to his predecessor.

Vasarely, however, transcends Suprematism, as he achieves a sense of spatiality with abandoning the traditional perspectivity and uses merely contrast to create an illusion of dimensions.

Hommage à Malévitch was also inspired by his life in Gordes: the sunrays filtering through the window arrived in an acute angle at the corners, and he realised the interplay of angles and the positive-negative interplay between light and shadow. This black-and white, binary world reduced to squares, circles and ellipses will be later populated by variedly manipulated grids that give an impression of a three-dimensional shape. One of the most illustrious examples of this trend is Dobogókő (1957-59) – unfortunately, the name tag of this painting says Dobkő, and this is not the only incorrect name tag at the exhibition.

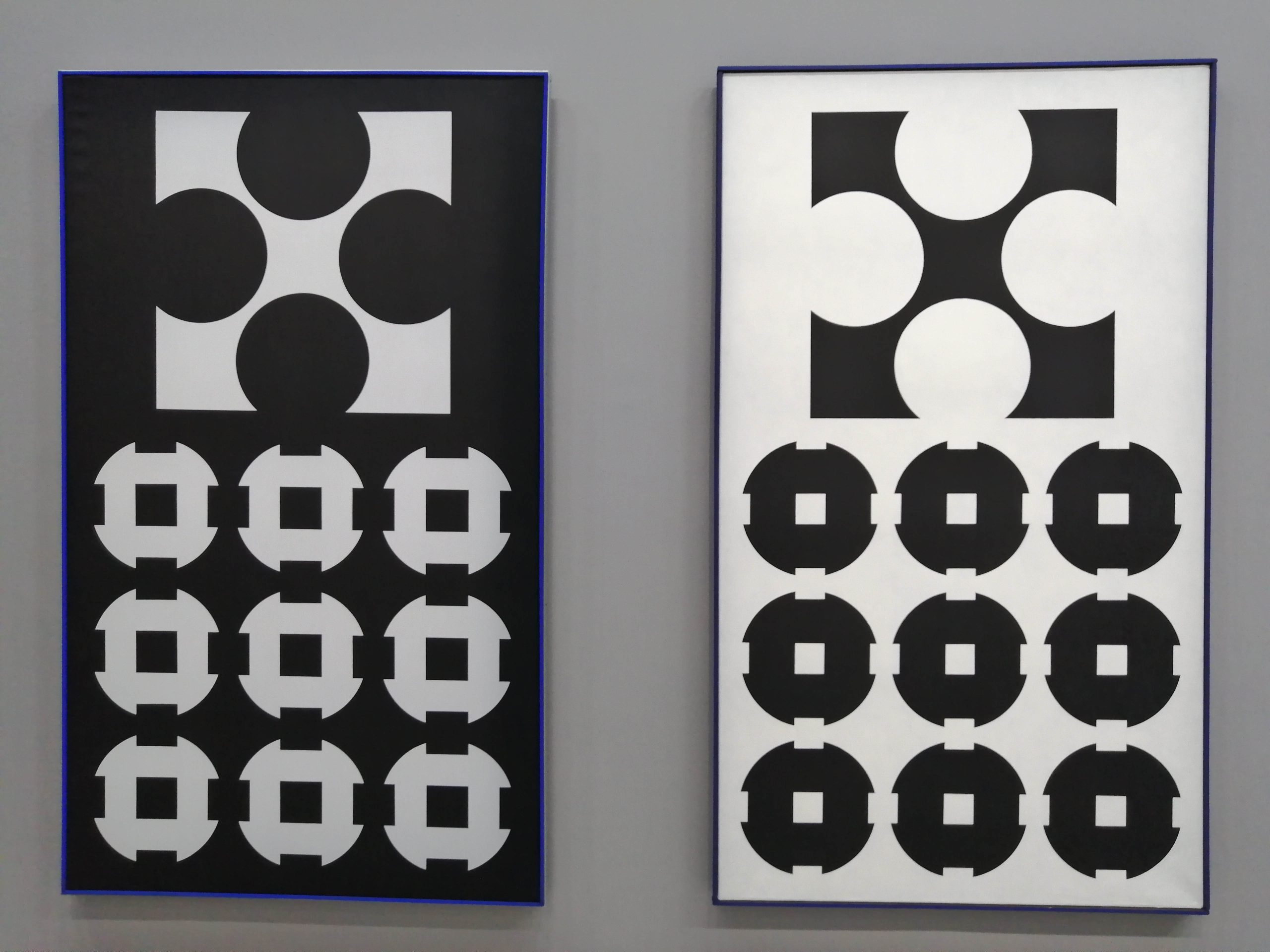

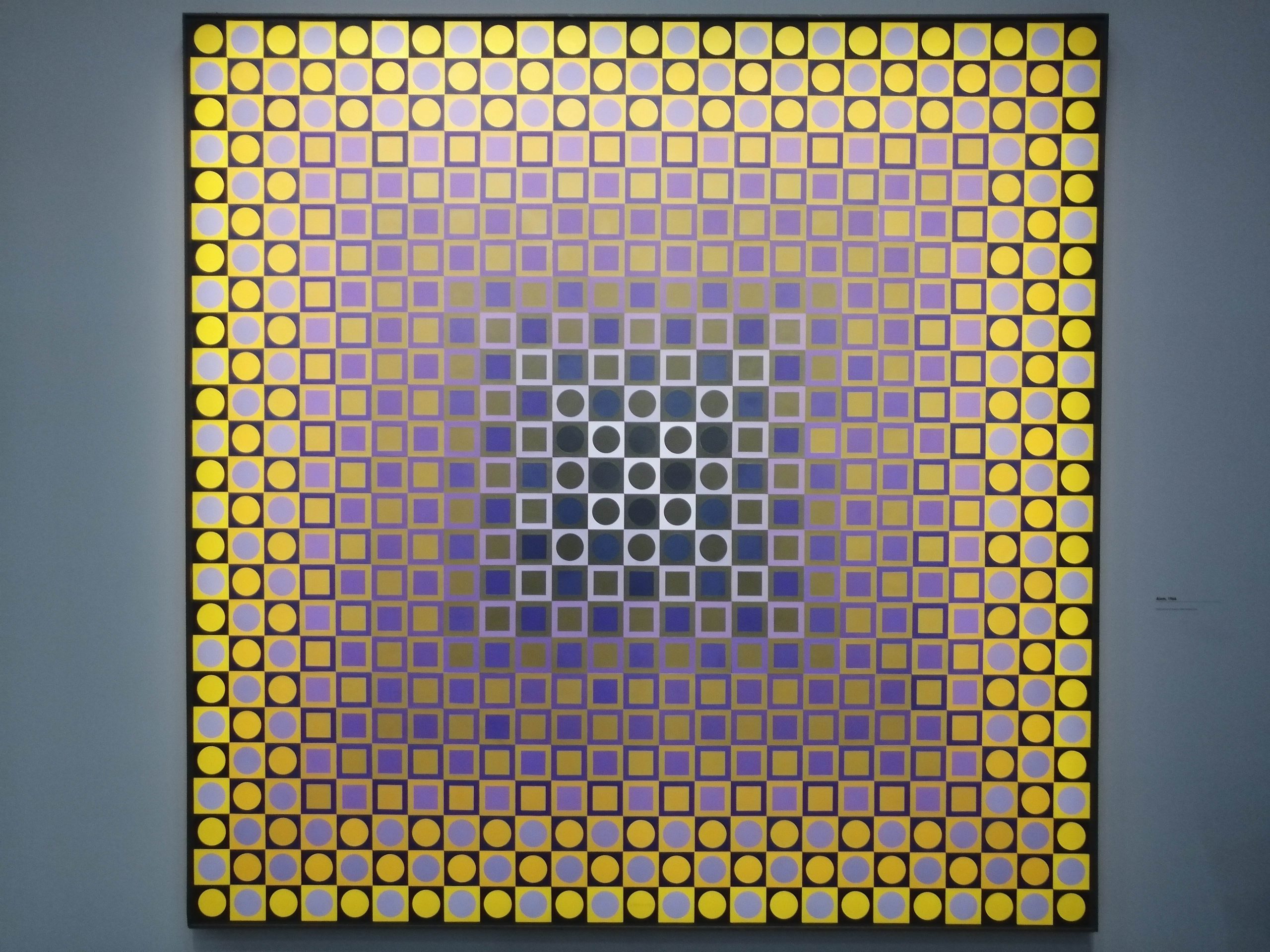

It takes only one step further to reach the series of painting based on sheer symmetry and geometry. The black-and-white, positive-negative polarity can be interpreted in the light of the then-nascent cybernetics as a visual binary system that Vasarely aimed to define in the 1950s. The diptych Procion perfectly illustrates the combinatorics of squares and circles, the negative and the positive.

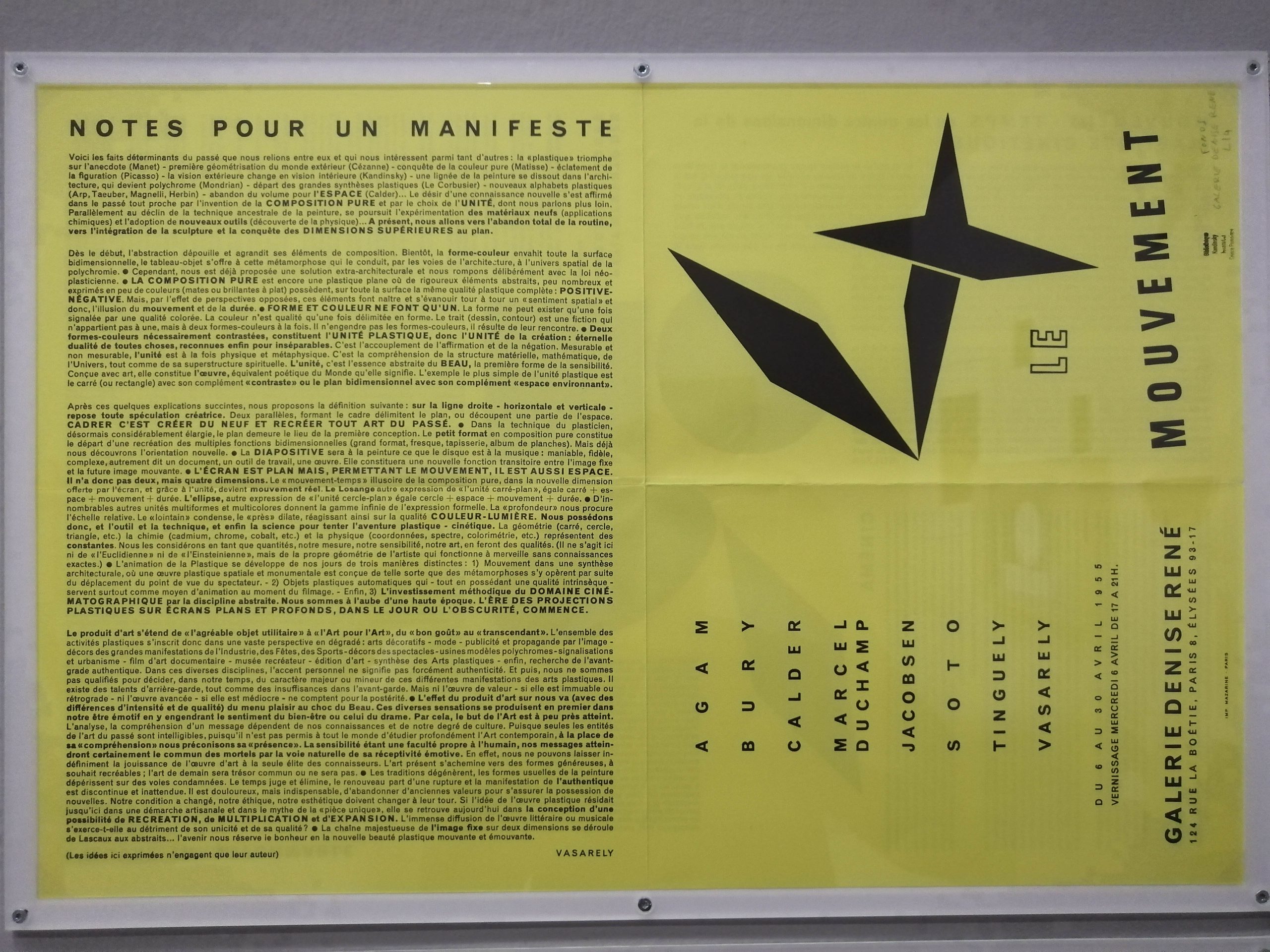

The exhibition also covers the Le Mouvement exposition, curated by Galerie Denise René in 1955. The backbone of the exhibition was the works of Marcel Duchamp and Alexander Calder, but it also provided platform to artists who popularised kinetic art (Pol Bury, Jesús Rafael Soto, Yaacov Agam, Jean Tinguely, among others). Vasarely was not only among the exhibitors with his geometric works printed on plexiglass, but he was one of the authors of the so-called The Yellow Manifesto, which announced the new kinetic-plastic beauty, the illusion created by the interplay between movement and perspective. One of the most interesting objects of this exhibition was Spiral by Soto, which can be read as the reinterpretation of Duchamp’s Rotative Demi-Sphère. However, Soto’s painting is not a moving object, the kinetic illusion is triggered by the changing of the perspective, the superimposed concentric circles can be seen as the precursor of op-art. Vasarely’s Naissance (1958) from this period reinterpret Constructivism in the geometric forms broken up by black-and white lines (see also Ilava, 1956), while there are experiments with distorting the two-dimensional grid into a three-dimensional illusion with concave and convex forms (Vega, 1956). Similarly to Soto’s Spiral, Vasarely’s Bi-forme (1962) plays with reflection and perspective, offering a kinetic illusion of geometrically abstract black-and-white lines. However, spatiality also plays a great role: the lines are engraved on two parallel glass panes, and with the changing of perspective, these lines slide along, and this dynamism transforms the work.

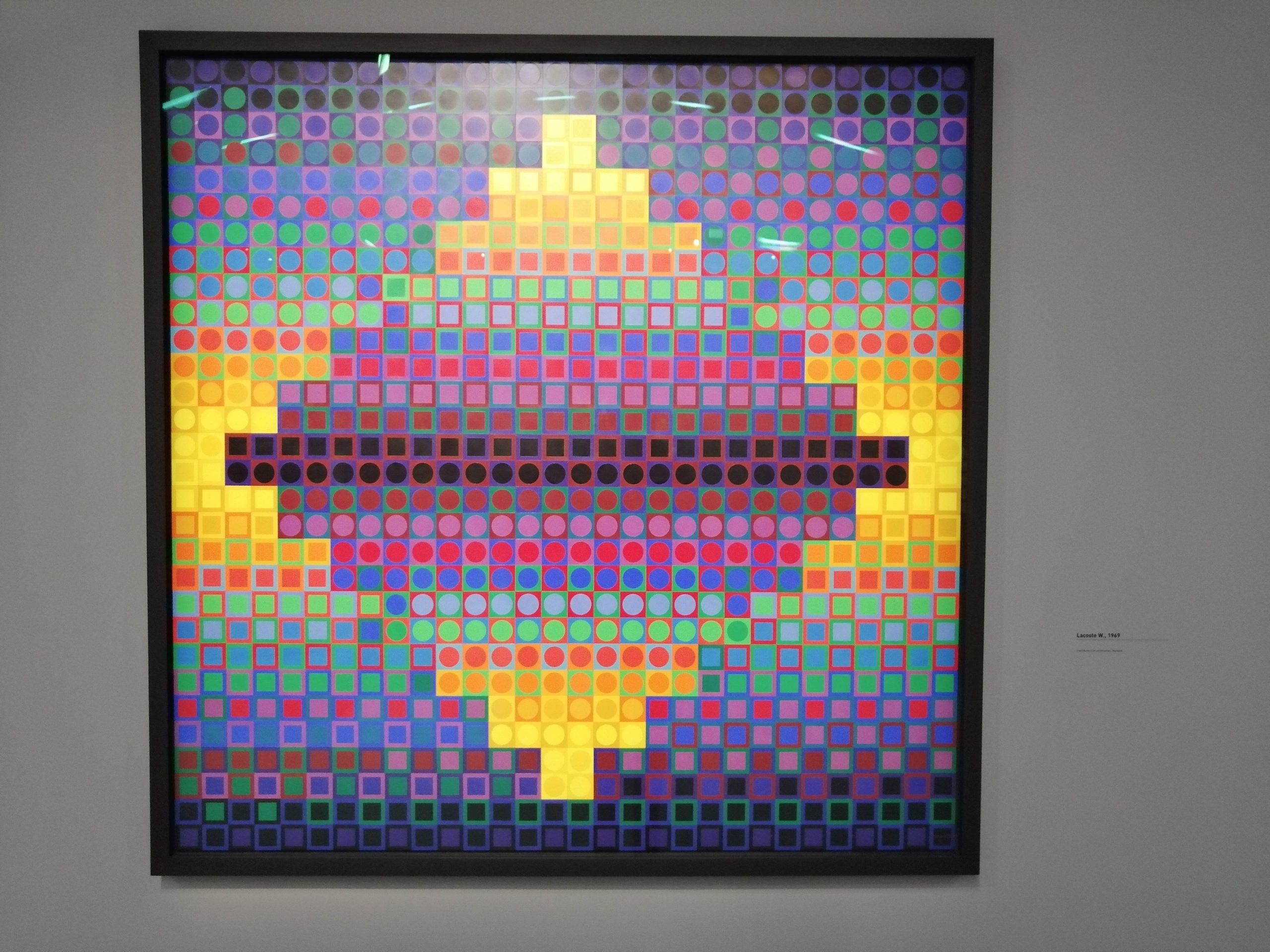

An essential stage of the experiments in the 1960s was the creation of the so-called “plastic alphabet”, a language based on the lexicon of six geometrical shapes and the grammar of the primary colours. “Complexity thus becomes simplicity. Creation is now programmable”, he wrote. This visual alphabet, described as “planetary folklore”, can be interpreted not just as a programming language based on combinatorics, but as an early writing system, as some kind of picture-writing as well. Therefore, the pictures created from the plastic alphabet can be considered as some sort of visual texts (Lacoste W., 1969; Alom, 1966). This abstraction can be represented in ceramics or even in plastic arts (Alom, 1968). The most striking element of this period is, however, is the logical game to use the signs and colours as interchangeable items, and by creating series of combinations, the image is changing as a kaleidoscopic work of art. The artist no longer offers a final product for the spectator, they are part of the creation process, the game. Op-art has been so widely used that it would be pointless to list and analyse every instance of its omnipresence.

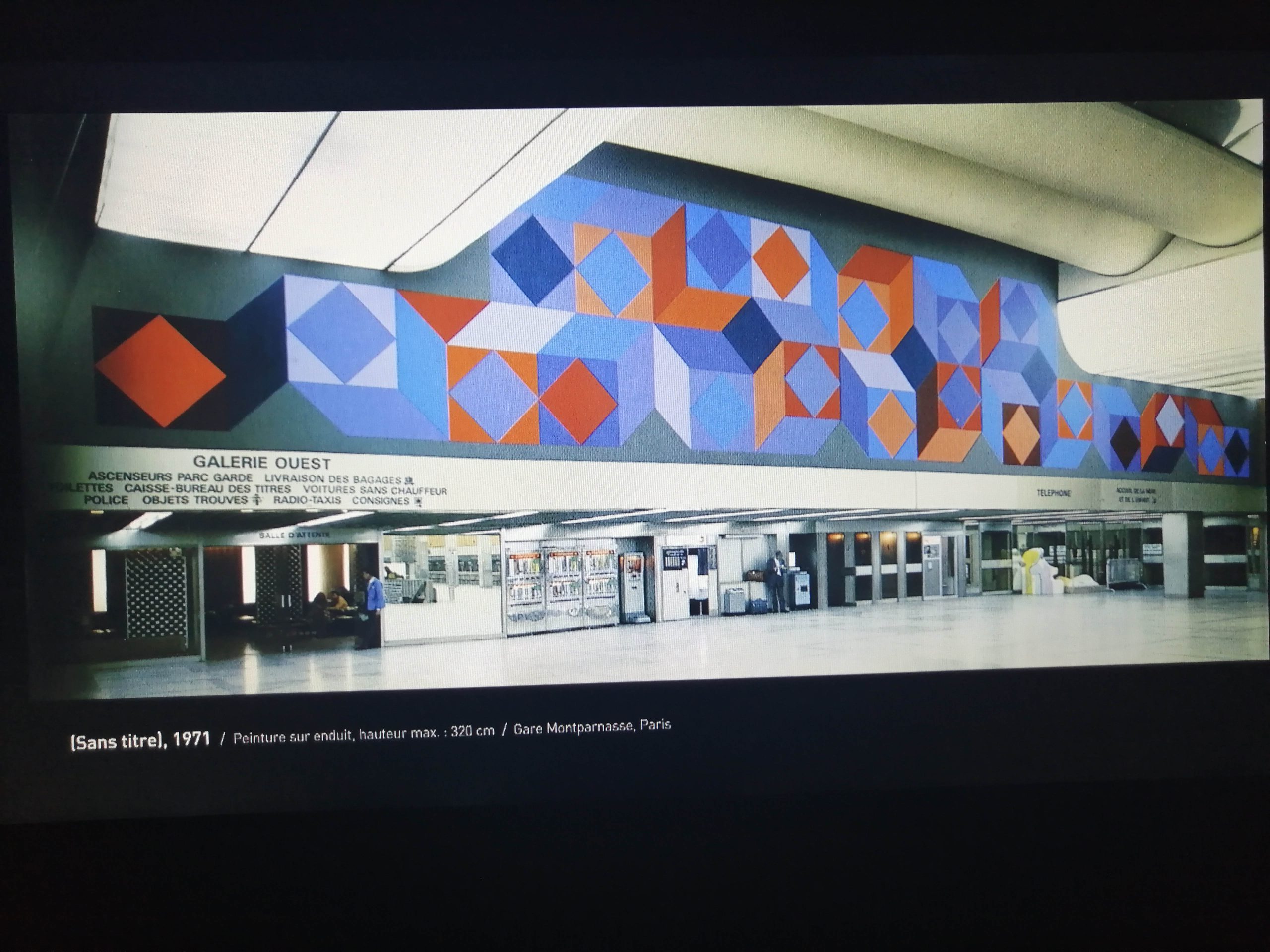

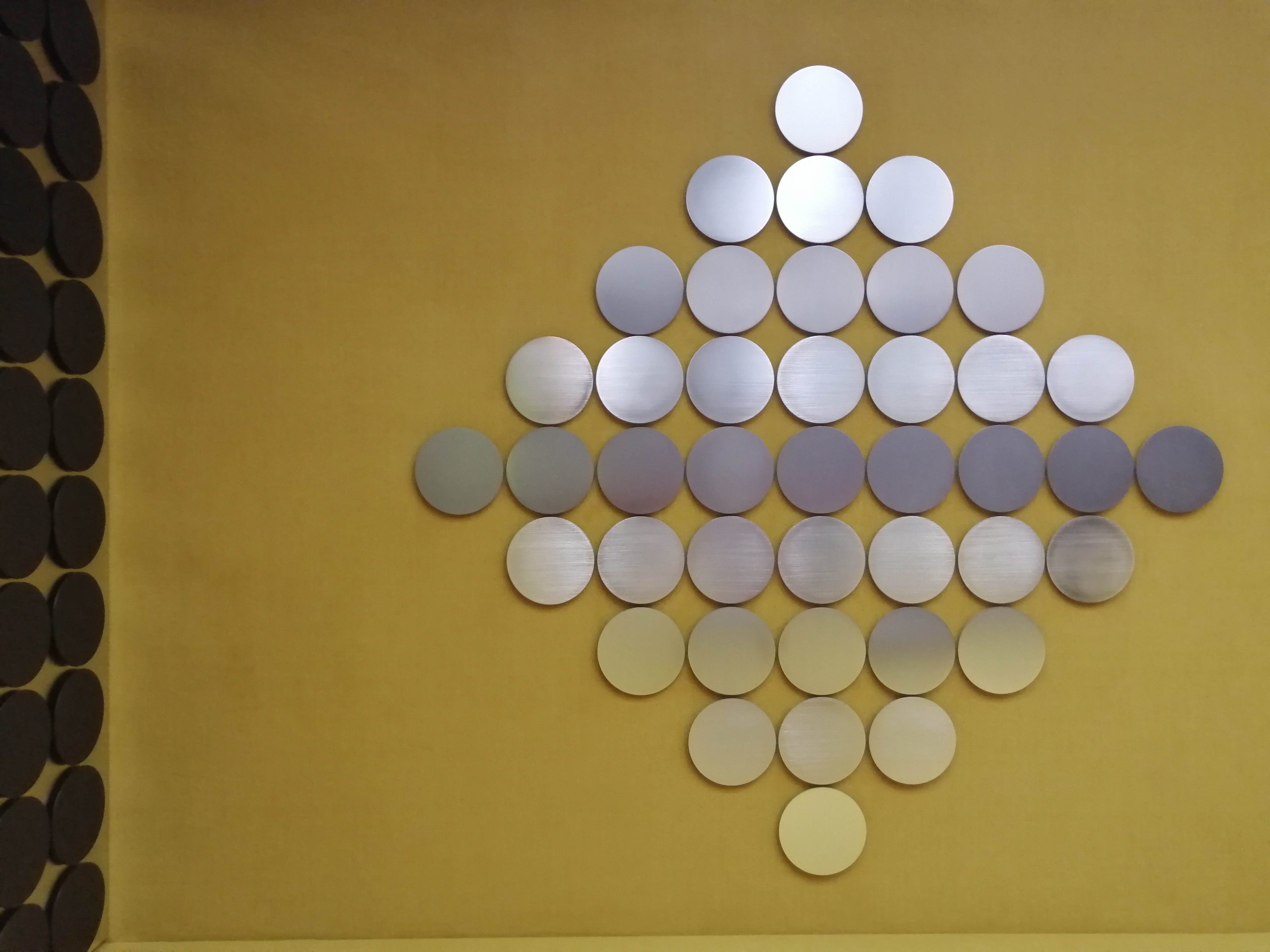

Op-art is still seductively elegant: just take a look at the cool and exquisite covers produced for the French publishing house Gallimard, the Renault logo, the interior design of the 1960s (e.g., metal circles on beige walls), and the geometric fantasies adapted to architecture.

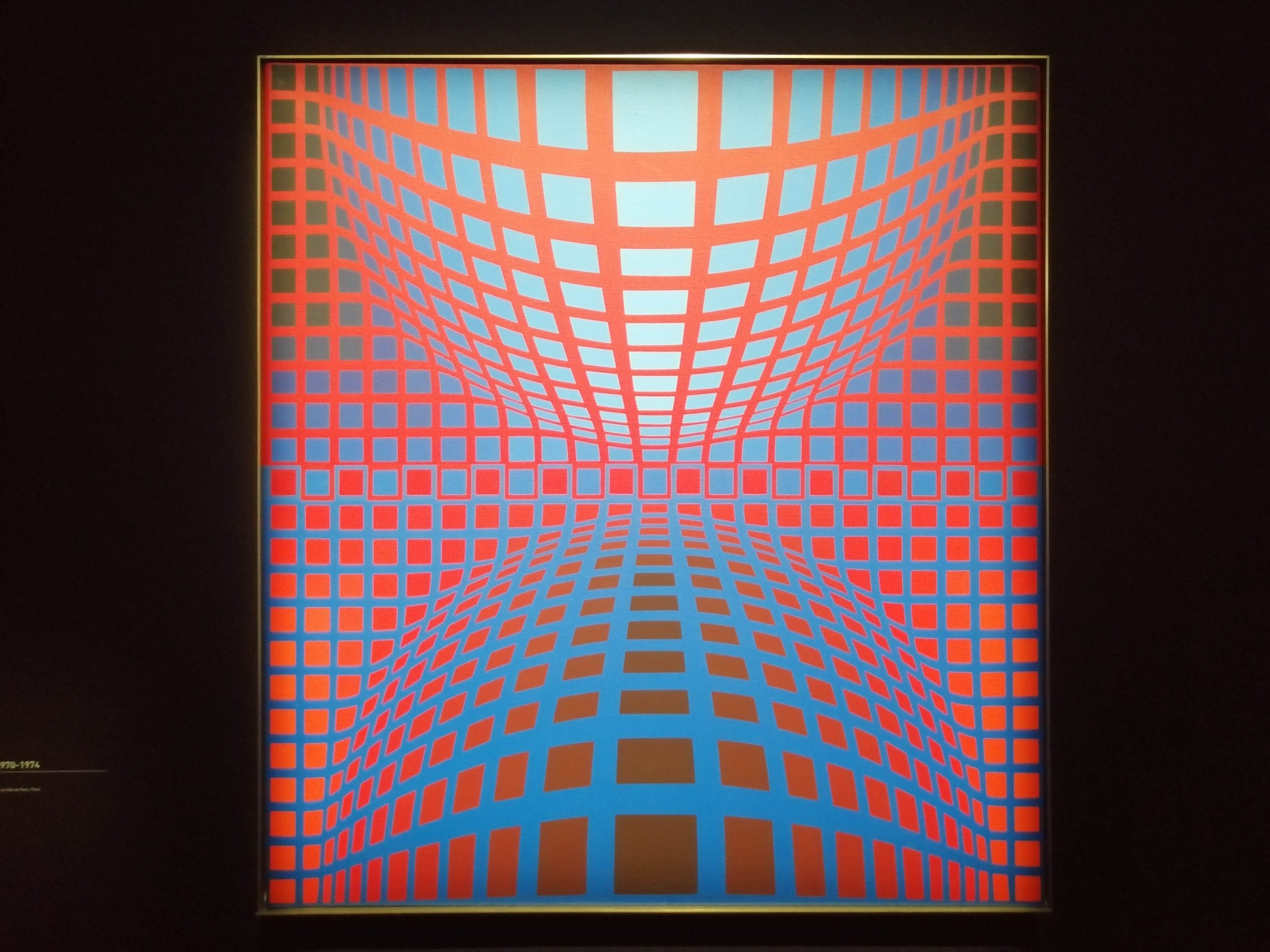

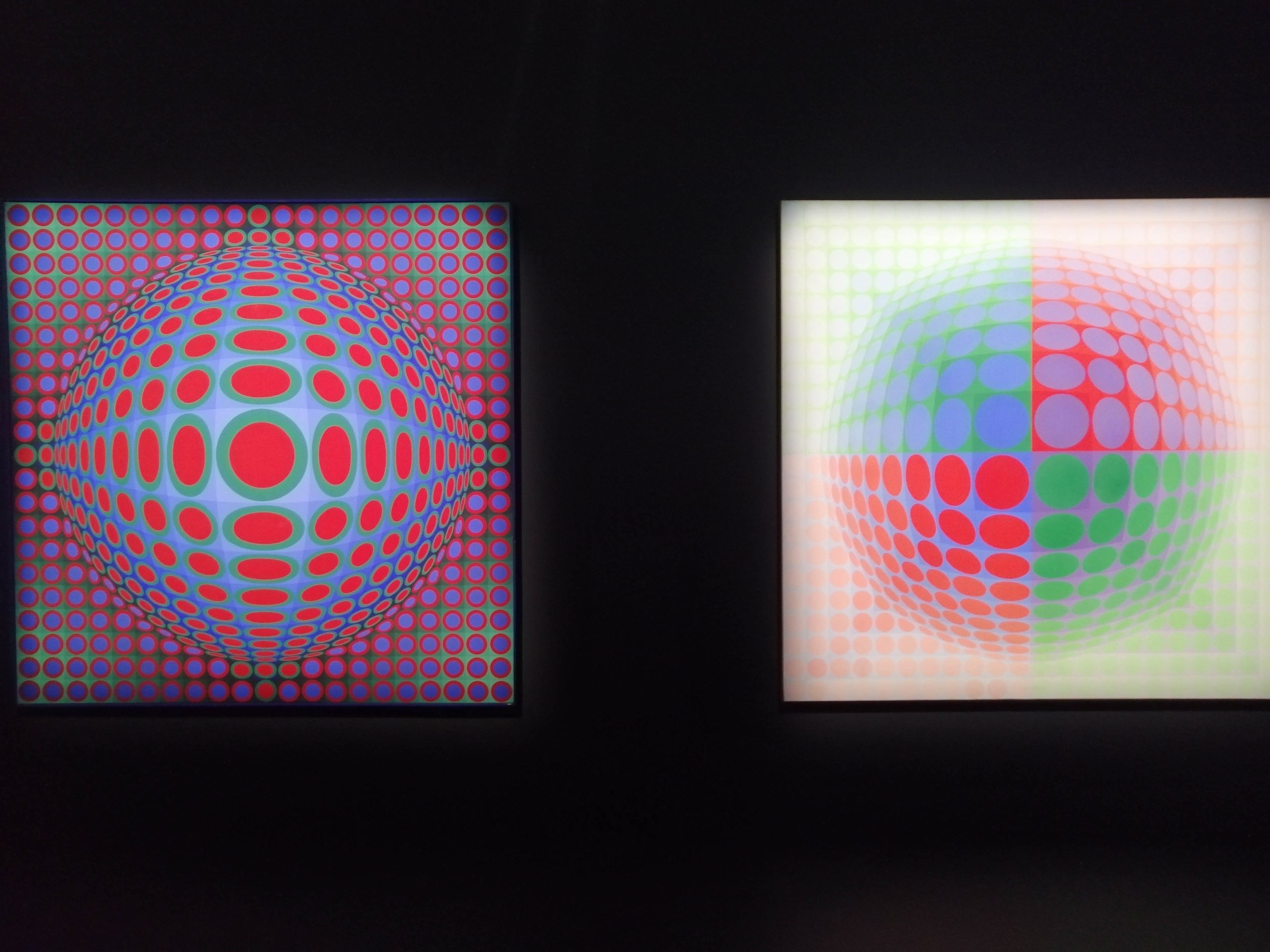

From an architectural point of view, the façade of Gare du Montparnasse is a perfect example – something I saw yesterday without realising whose work it might be. The full-fledged optical magic, however, from the most mature and emblematic period of Vasarely, is presented in the last room: the “sound of quasars”, the “interstellar landscapes”, the “beating of pulsars”, as he referred to these multidimensional fantasies. Due to a perfect light design, the optical illusions indeed seem three-dimensional, the interaction between lights and abstract geometry creates a theatrical effect, the image only works then and there, in that very moment when the perspective of the spectator changes in space. These images presented as a photograph easily lose all their magic, but if you are reluctant to view such sheer abstractions in galleries, saying they are the same as their reproductions, you should visit this last room (e.g., Meh 2, 1967-1968; Vega Zett, 1971; Opus III, 1970-1974) to experience firsthand the mathematical magic even of the most matte pictures of Vasarely.

Ha tetszik, amit csinálunk, kérünk, szállj be a finanszírozásunkba, akár csak havi pár euróval!