Man Falling Apart in the Shade of Trash

Sex toys, stuffed animals and trash, botched together, impaled, glued. Metamorphosis and anthropomorphising through light – the vision of man expelled in a world of shadows. Tim Noble and Sue Webster has been building art installations from trash since the second half of the nineties. From household garbage to metal waste and from used and thrown-out sex toys to stuffed or mummified animals: they use everything to bring to life and to re-create man – according to their own ideas.

The “recycling” of disused objects, ready to be disposed, can be traced back in the medium of art to Duchamp’s bottle rack and urinal turned upside down. Later, in the second half of the 20th century, similar objects, deprived of their original function, worn-out but reinvented, started cropping up one after the other in fine arts. Back then, it was not primarily for ecologic reasons, but rather as a kind of statement about the relationship between art and life and about the issues of consumer society. This was also the case with arte povera (“poor art”, a term introduced by the Italian art historian Germano Celanto) that appeared at the end of the sixties – a trend which defined itself opposed to unnecessary accumulation of consumer society, to the overproducing strategies of the market and the artistic and art market traditions. The term does not refer to the quality of the artworks or to the social status of their creators, but to the raw materials incorporated into the artwork. Artists started to create their works using materials deemed worthless: rags, tires, newspaper, household waste or even perishable materials (e.g. fruits and vegetables no longer fit for consumption), creating value from the valueless, the disposable and the reusable through their art objects.

However, these creations of Noble and Webster are not clearly and solely related to the trends of arte povera. Their “reused” trash heaps confront us with the epoch of the Anthropocene, dating from the commencement of human intervention into the life of the planet, which has left its traces everywhere on Earth. At the same time, trash is elevated to a new rank through its incorporation into the exhibition space. The Anthropocene cannot be interpreted only as a descriptive concept: it is also endowed with the horizon of action in the field of fine arts (or in literature), going beyond aesthetic and theoretical categories. The Anthropocene trends in art are directed at conceiving the artworks in a wider context as well, not only as creations, but also as an event of human civilization and culture. The focus of the works cannot remain fully restricted to humanity: thinking the Anthropocene allows for the mise-en-scène of pre-human, post-human and sub-human perspectives.

So, besides arte povera and trash art, based on eco-critical thought, now enjoying a growing popularity, the Anthropocene represents the active, theoretical and aesthetic horizon of the artworks created by Noble and Webster between 1997 and 2012, which operate with the play of light and shadow. These shadow portraits, manufactured from different objects, could even be considered – from the perspective of the history of influence – the rethinking of the eccentric 16th-century artist, Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s allegorical portraits composed of fruits, animals and various objects. Besides the artworks more closely examined below, the artist duo’s acrylic painting titled From F**k To Trash, constructing human profiles from trash and animals, shows even more similarity to Arcimboldo’s works.

In the installation titled A Couple of Dirty Fucking Rats, the “fucking” rats of the title are created through the illumination of a heap of street trash. These omnivorous animals, feeding even on trash, are some of the best-trained survivors of the animal world, the true masters of adaptation, able to survive even under the harshest conditions. We humans fight against them and exterminate them, while expanding our own habitat at a much faster pace through accumulating excessive amounts of garbage. After man will have drowned in his own filth and will have undermined his own existence, the time of the rats will come. One could say – with a bit of exaggeration – that the rats’ habitat is growing as the humans’ is narrowing. After all, it is no coincidence that rats are considered the No. 1 lab animal due to their intelligence, as it is also not happenstance that the installation captures the moment of breeding, the image of the future as it emerges from the trash.

Dirty White Trash (With Gulls) is one of Noble and Webster’s first installations on this theme. The artists have collected their own household waste, collected over a six-month period, to be used as raw material for the installation. Thus, the two figures leaning on each other of the silhouettes projected on the wall are, in fact, equivalent to a half year’s volume of trash. This is what man is, says Noble and Webster. Or, indeed, this is what we ourselves, the artists are, not only due to the fact that it is our waste – as it is common knowledge that the creators usually represent themselves through their installations. Their self-reflection may strengthen the feeling of the artworks’ authenticity, inspiring similar eco- and self-critical thoughts in its recipient. This shadow couple, casually leaning on each other, smoking and drinking, may to mind associations of hedonism and the worship of excess – unmotivated actions resulting in the installed trash heap’s metamorphosis into a framework for the negative silhouette of a kind of optimistic nihilism and carelessness. Meanwhile, the man-made (stuffed) seagulls heartily snack on the garbage heap, which is to say, from the human figures projected on the wall. By contrast to the shadow rats, the seagulls, these “rats” of the seas, take on tangible form and are much more real than the human presence, only perceivable through the light. It is as if the two artists would designate the animal again as the survivor against us humans, at least as far as the fight against trash-overdose and outliving garbage.

This animal theme is continued by the installation titled Kiss of Death, composed of stuffed animals and animal bones: 34 taxidermically bodies, including rats, weasels, jackdaws and ravens. The latter, as the messenger of death, plays a central role in this collage, representing two human heads stuck on poles in the background. The bird stands out among the various elements of this installation, its silhouette is clearly distinguishable in the shadow world as well. In fact, this bird – considered to be one of the most intelligent among its species –, is preparing to feast on the eye from one of the human heads. Hence, the artwork raises the same question as the previous two: positing itself against the anthropocentric worldview, it asks whether it will really be us humans, arbitrarily posited at the apex of the evolutionary triangle, who will be the great “Survivor” after all? In order to represent the importance of this question, the artists later created an entire “trilogy” on this theme, based ont he Kiss of Death, titled Facts of Life.

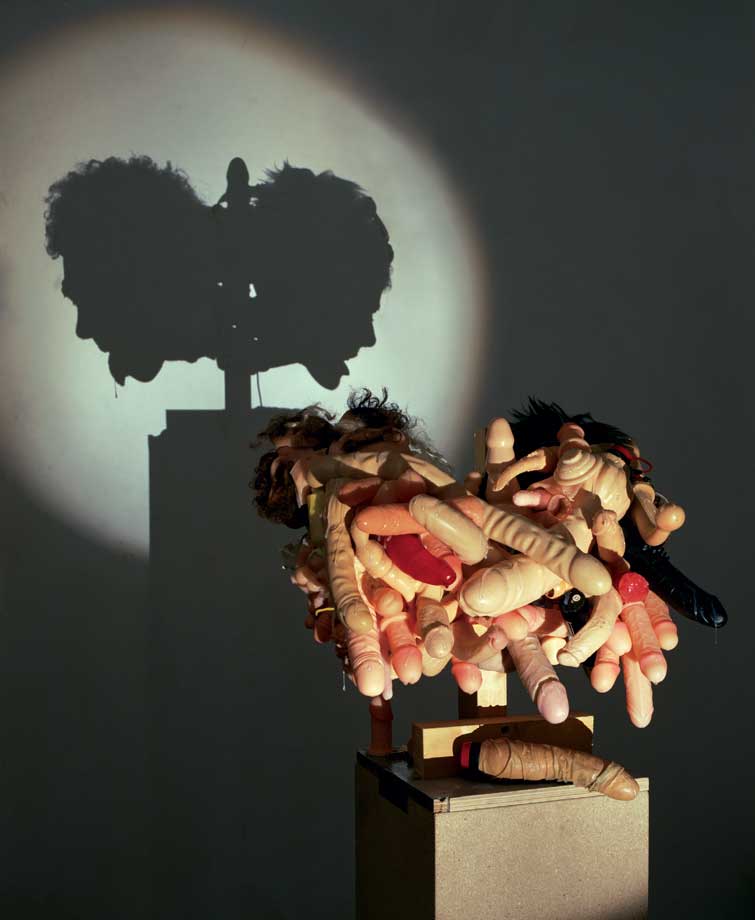

Although a bit out of (thematic) line, the installation Double Header Double Pleasure is also worth mentioning due to its radicalism and shocking character. In this case, the anthropomorphic metamorphoses projected on the wall using garbage and stuffed animals is substituted with the collage orgy of the disused sex toys’ (dildos and plastic cunts) metamorphosis. It is again something artificially created (but all the more tangible and firm) standing in contrast with the organic and living, and thus elusive and uncertain. The penis imitations of different sizes, colours and shapes – similarly to the alcohol and the cigarettes – may serve the representation of pleasure and its sources, also associated with the desire dropping in liquid form, as saliva and/or semen from the tip of the male heads’ tongue. The human profiles, the markers of identity emerge from an infertility that is aimless and futureless – from the perspective of the preservation of the species –, from the plastic and silicone that is “immortal” or, in any case, that will outlive the individual, its user.

Finally, to leave no false illusions regarding the future and for us to be deprived of all that is human (in the current sense), of all anthropocentric hope, let us take a look at the installation titled Falling Apart, created from the garbage produced by Noble and Webster between January and March 2001. The artists have used spatial dimensions as well in this case, since the female head is the larger one of the two heads that are “stemming from the same root”, and is thus perceived to be closer to the viewer. However, this installation is not about illustrating any gender dominance – or even if it carries such connotations, they are surely overridden by the question referring to the human species as we know it today. This illuminated trash heap projects the shadows of two post-human beings on the wall.

Falling apart, hollow and fragmented, these machine faces are focused on the critique of the humanist ideal of “Man”, defined as the universal representative of human existence.

Thus, the anthropomorphic garbage – apart from the “fucking rats” or even starting with them and now reaching the end of the line of an evolutionary process – finally shows its true colours, providing a vision of the future for the human recipient of the artwork: these pieces of garbage, collected here during a three-months period, form here a disintegrating final product (of shadow) that is resembling man.

These installations contrast the eternity of plastic, the conservation of the living and organic in the stuffed animal, the metamorphosis from organic to inorganic, with the momentary character of man (and humanity), exposed to his environment and to the circumstances. After the spotlights are turned off, all that remains is nothing but the trash, the sex toys and the stuffed animals.

“Arte povera has essentially substituted the representation with the represented (recalling the main thesis of general linguistics’ ‘great elder’, Ferdinand de Saussure, about the signified and the signifier), creating the memory of space in contrast to its concrete presence. In fact, it is probably more accurate to say that the spatialized objects of arte povera are symbolic in this respect, representing their own ideas […], and are not representations of something else or in the service of representation in the traditional artistic sense, but simply exist, without pointing to anything else but their own idea” – says Katalin Balázs on the portal Napkút. The art installations of Tim Noble and Sue Webster reflect on this idea as well, while also turning it inside-out. If we set aside the silhouettes projected on the wall, the momentarily illuminated additional meaning, then the garbage, the trash heap, the stuffed and mummified animal carcasses carry meaning in themselves: their presence offers social, political, economic and ecological criticism in the artistic space. Put into the spotlight, they reveal the criminal (man), his victim (also man) as well as the survivor (the rat), while displaying the image of the future that is projected from them, of the posthuman creature.

Photo source: http://www.timnobleandsuewebster.com

Translated by Lóránd Rigán

Ha tetszik, amit csinálunk, kérünk, szállj be a finanszírozásunkba, akár csak havi pár euróval!