Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful

Without a doubt, Marina Abramović is one of the most intreguing artists of our time, who was a pioneer not only of Tito’s time, but also of contemporary art. If it wasn’t for her, our ideas today about conceptualism, performance art or body art would be completely different; what’s more, we may not have known this deeply the magic triangle of art which connects the artist and their audience with the mesmerizing threat of risk and danger. Abramović’s life work has become an inevitable chapter of art history. The exhibition of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, which bears the title The Cleaner, showcases not merely the genesis of the Abramović-phenomenon but also her lifelong artwork.

We could suspect, although we have probably hardly given it a thought, that the young Marina’s career as an artist started like any other artist’s. We are in 1960s’ Yugoslavia, where the greatest desire of the talented teenage daughter of a partisan military couple is to finally change her watercolour palette for oil paint and become a real painter. As a surprise, the exhibition presents the dedicated and hardworking teenager who tries to discover what art is, and how she fits in it.

Her cloud-cycle is a witness of all the changes in her artistic style. It shows how she embraced new and new forms and grew beyond them, then searched for other possible answers compressed into new visual languages from traditional visual representation to avant-garde futuristic and surrealistic images and collages and to her first conceptualist work, the peanut cloud (Cloud with Its Shadow, 1971). Looking at the series, the consistency which has taken her along this path, to the first milestones of her particular art, seems self-evident yet overwhelming.

The peanut is something new in many respects. Firstly, it is an object which was not fixed onto the canvas, but at a distance of some centimetres from it, in order to break the light which falls on it. If it wasn’t for the light, the background would be overcast with natural shadows. Secondly, Abramović placed this object into a new context, and through the invisible prism which she thus juxtaposed to it, we see it in an unnatural way, as a cloud. This was the moment when she realised that as an artist she had a much greater freedom than what she had hoped for.

Abramović asked more and more complex questions from herself and while answering them, she gradually moved totally over to a conceptualistic expression. She was interested in simple things and everyday thoughts that we usually ignore, like whether we can make the same mistake twice. In answer to this question, Abramović used a blank sheet of paper, twenty different knives and two tape players. She set one to record, and she began thrusting a knife between the fingers of her stretched left palm, at a faster and faster pace. Whenever she missed and nicked herself, she changed the knife. When she used up all the knives, she rewound the tape and listened to it. Then she turned on the other tape player, repeated the entire course of action while trying to reconstruct the mistakes she made in the first case. At the end, she played the two tapes simultaneously and left the room. After the performance was over, the audience listened to the overlapping rhythms while staring at the blood-stained paper and knives.

This was the performance called Rhythm 10 (1973) which made Abramović feel almost literally the taste of blood with her tongue, and from that point on radical gestures which she used in her performances often risking her own physical integrity became recurrent elements of her art. It has become a part of her being to challenge her audience to experience authentic human feelings. The message that she has been trying to spread ever since to reach as many people as possible is the importance of being present, being there, to recognize the transience of life, and give up unimportant things.

Abramović was the first artist who placed the responsibility for art in people’s hands. Not merely the responsibility which allowed them to harm her unpunished – like in her performance Rhythm 0 (1974) – but the responsibility for the audience to accept the risk of turning from an onlooker into an actor – like in Rhythm 5 (1974). This position is still uneasy today for people in her audience who are not comfortable with the limelight. In the cases when she put her own body at risk it was usually an onlooker who couldn’t bear any more to stay passive and helped her.

Abramović’s radicalism has manifested itself not merely in creating dangerous situations, but also in using new media. Her art is not about the body, or rather not about the body in the first place. The body for her is not more than an instrument, a medium, a mediator which takes the message to the viewer. In this sense it is self-evident that the clothes are just a disturbing factor which influences the viewer’s response. We are hardly perplexed by nudity these days, but we can only imagine how all this was perceived fifty years ago.

Nudity and the way how Abramović delivered her body as an object of art promoted the human body as a non-verbal advocate of the all-time truth.

The exhibition and the endless video documentation presented there shows how feelings and thoughts can be misunderstood without a third dimension. Abramović has not had exhibitions in the region for decades, she has always turned down her invitations to Serbia. She has never motivated her decision, art historians can only guess that she may not have wanted to degrade her previous artwork with a low budget exhibition. However, since her works – including the video recordings – are all in her private collection, we’ve had almost no chance of seeing them. Performance art is an art form that cannot be reproduced, its essence is the process itself which comes into being as a never returning event taking place at a specific place and time. Therefore it is utterly impossible to hope for a comprehensive experience merely based on snapshots.

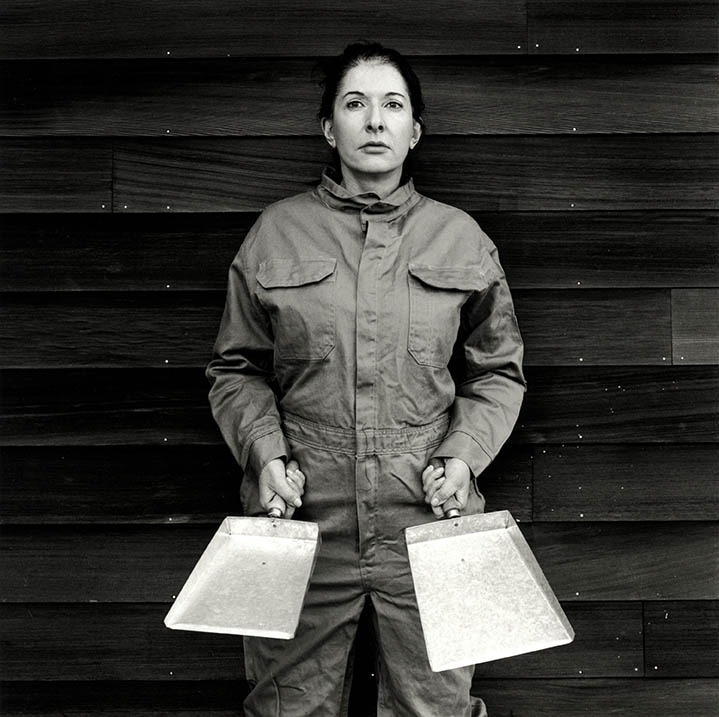

The best place to tackle this unsolvable issue is probably her work Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful (1975). The motion picture presents the absurd play in progress of combing and tearing her hair with a metal comb and a metal brush, which she continues until she hurts herself. The effect is enhanced by the artist’s repeating the sentences in the title like a mantra, which makes it even more contradictory as she is becoming more aggressive and hard-handed in combing her hair. The photos of the event were only faintly indicative of the feelings of pain, relentlessness and determination that the artist must have experienced, merely as a poor reproduction of the effect that the motion picture had on the onlooker.

A similar problem occurred with the work Rest Energy (1980), created with Ulay. The two bodies face each other, Marina holds a bow in her hand, and Ulay an arrow in his. Leaning back, they tense the bow and point the arrow to Marina’s heart. The performance lasted for 4 minutes and 10 seconds, while their accelerated heartbeat is heard via the small microphones they wear. The physical strength, the tension of their focussing on not to let go of the bow and arrow can hardly be experienced through the static images. Especially because in this particular performance we can hardly tell if it’s the eighteenth or the 213th second. But seeing the performance from beginning to end, perceiving the passing of time and hearing the intense heartbeat of the two persons, we are indeed the witnesses of a game of life and death.

This performance – perhaps precisely because of the risk it involves – is one of the climaxes of Abramović and Ulay’s common life and art. That is why it conveys such a dramatic contrast that the exhibition presents the performance The Great Wall Walk (1988), the story of their separation, opposite to the previous performance, or rather from an opposite angle, turning its back on it. Clearly, after this experience Abramović has walked a completely new path, unrelated even to her previous solo career.

Her relationship with Ulay ended completely after her walk on the Great Wall of China. Decades passed without them meeting again. Then, in 2010, at the New York Museum of Modern Art, during her performance lasting between March and May, entitled The Artist is Present, Ulay surprised the artist. The video which captured the couple of minutes while the eyes of the former couple connected and took them back to their finest memories has become viral in international press, and it was a revealing moment for many when Marina reached out and held Ulay’s hand over the table. After this encounter they reconnected, and they also gave an interview together at the exhibition The Cleaner.

Her later works are wiser, more philosophical and spiritual. They mirror the changes in the artist’s life. Let us not forget that the young and crazy woman who, ignoring all the risks, passionately searched the answers for questions she couldn’t expect anyone else to answer for her, has grown up. She no longer wanted to exhaust herself, to push herself to the extremes. Her interests turned to other directions too. She created a performance on the Serbian war for the Venice Biennale in 1997 (Balkan Baroque), memories of her childhood in which she confessed her life to a donkey (Confession, 2010), and also tried to find the meaning of the eroticism of Balkan peoples (Balkan Erotic Epic, 2005).

One of the most outstanding performances of Abramović’s late work is the aforementioned The Artist is Present (2010), where she kept eye contact with more than 1600 people for 736 hours. The viewers could see also the people who sat opposite to her, people being emotional, kind, smiling, sad, serious, uninterested and provocative. All this while Abramović stayed the same: interested and accepting. This performance, like some of her other works, is also extraordinary by its length, because Abramović’s unaltered, unprejudiced way of relating to people here, which is one of the greatest challenges of our age, needs a very strong and sustained presence.

The exhibition The Cleaner was an exceptionally elaborate one. The multimedia tools convey a smooth experience of performances. The descriptions lead the unprofessional viewer through the exhibits with precision, and the interviews let us see a less known side of the artist.

There is still something that keeps us from a completely satisfying experience of the exhibition or of the impression of what we see, and that something is Abramović herself. Her attempt of turning things inside out and showing their absurdity only works if it happens amid authentic circumstances. But how authentic can the message be if the interpreter becomes inauthentic? Can we believe indeed that the most important thing is to experience the present if the one who tells that to us cannot accept her present self, with her current age and wrinkles? Now in her seventies, Marina Abramović has become an addict of aesthetic treatments. And while of course her creative work should not be evaluated in the mirror of her vanity, still – thinking of her performance Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful – it is the forced target which distorts the natural beauty, which is difficult to disregard.

Marina Abramović: The Cleaner

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade

September 21st, 2019 – January 20th, 2020

Curated by Lena Essling (Moderna Museet), with Tine Colstrup (Louisiana Museum of Modern Art) and Susanne Kleine (Bundeskunsthalle).

Translated by Emese Czintos

Photos: Marco Anelli, Bojana Janjić / The Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade

Ha tetszik, amit csinálunk, kérünk, szállj be a finanszírozásunkba, akár csak havi pár euróval!