The Frightening Hedonism of the Mirror Labyrinth

Dorit Margreiter, the excellent Austrian photo, installation and video artist, is perhaps less known to the Eastern European public. She lives in Vienna and Los Angeles. The main topic of her art is the relationship between the landscape, the spatial structure and the lifeworld: she sometimes projects architectural schemes onto the unruly existence, arranges destruction artfully, transforms into fiction what is direct and real, confronts the digitally designable, seemingly timeless dream world with temporal reality. Even her non-filmic works are film frames or film sets.

At least this is the impression one might get from her exhibition organized by mumok, with Mirror Maze (2019), the video of a mirror game filmed with a static camera as its centrepiece. This film was made at the Prater amusement park in Vienna, in the Calypso mirror labyrinth, a “historical” enchanted palace built in the 1950s. It is not only our sense of orientation, clear sight and reality that are lost in the sparkling mirrors, but also the usual perspective from which we imagine to see ourselves. This artwork, which can be conceived as the spatial model of the past and remembrance and elusiveness, continuously belies itself, forcing the control-deprived viewer to constant revision – which can be both entertaining and scary.

The conflict between the designed, stable space and the perceived, unstable and insecure world mobilizes several cultural historical allusions from the shadows of Plato’s famous cave via the delirious world of Calypso up to Alice, who wanders lost in Wonderland.

A similar attraction is exercised by Margreiter’s Broken Sequence (2013), which focuses on an amusement park built in Beijing in the 1990s. Asia’s largest amusement park buried was built on a medieval village, substituting the ancient architecture with the technically precise layout of an illusory world. The irksome awareness of the controlled illusion constantly puts Margreiter’s pieces into ironic parentheses: she is not interested in the absurdity of the Asian Disneyland, but rather in the functions conferred upon the layers, copied over and repressing each other. The amusement park was shut down as early as 1998, the dream world of yore lies in ruins, and its magical-mythical childishness only recalls the catastrophe hedonism of a post-war world. Nothing but dust and plastic debris. The remains of American-imported kitsch and the sentimentalism of escape. The timeless fantasy world distorted by the gnaw of time.

The rather fresh piece titled Boulevard (2019) is an especially inspiring film that was shot in the Neon Museum of Las Vegas. It offers a more prominent role to decorativeness and sensuality, Las Vegas’s illuminated and alluring body, architecture and illusion, practical communication, advertisement and nostalgia for a technology that is slowly becoming obsolete slowly reveal their outlines or flash before our eyes. The game is in a central position here as well: the world of the casinos and amusement arcades associates the perceptions of fate, luck and dreams, encircled by the sands of the Nevada desert. Night culture, nocturnal existence, illuminated pleasure and gleaming illusions. However, Margreiter also knows full well that the lights will face, the neon technology will become outdated, and the casinos will close.

The play of illusion between reflection, light and found material irradiates Margreiter’s kinetic spatial installations. The interplay between the suspended objects and debris, sometimes shining and sometimes so light as to barely reveal their material substance, has a strong musical character and could be associated with John Cage’s chance music. The great classics of kinetic sculpture (with Alexander Calder’s presence almost palpably present), the traditions of the genre intervene into the interpretation. At the same time, Margreiter’s structures also integrate the modern technological procedures of architecture and the nostalgia for specific spaces, as zentrum (2006) evokes memories of the destruction of a socialist cultural centre from Leipzig and its once flourishing design culture.

In her video installation titled Jock (2001) Margreiter plays baseball. She wears a helmet and gloves, prepared to meet the balls spat out by the machine with the bat. The cameras have been mounted on the machines and the artist herself, the event, is seen from the perspective of the balls that are served at five-second intervals, revealing the system of relationships between body and reaction, provocation and hedonism.

The conflict between the physical force capable of intensifying the reactions of the fallible and unpredictable female body and the technical intellect behind the rhythm of the machine is also present in this situation, thus bringing us immediately back to one of Margreiter’s basic themes.

The trajectories of the blue balls in front of the blue sheet and the fixed moment of the flight: more artistic than even the video material, the illusory copy of that which is deemed to be „more real” in the video, while being just a technical matter in both cases. The dots that put on the photos may be regular planets, spots, spot-painting or even cyanotypes. Now it is not the gaze of the barrel of the serving machine that stares at us.

For Margreiter, both the digital world domination of the silicon valley and the material character of reality are artistic themes. At least Silicon Valley (2019) convinces us so: unreality (or the hyper-real) entering into private life provokes a new way of seeing and perceiving time.

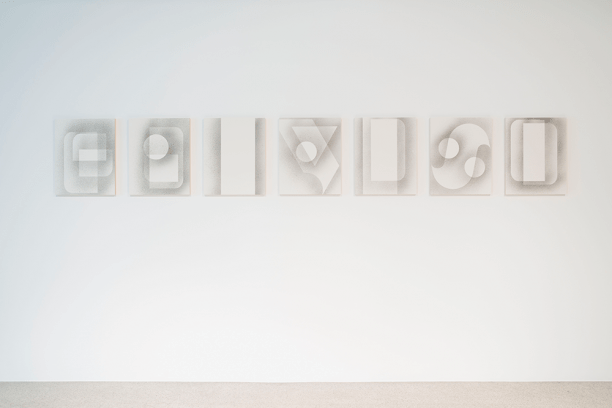

Black-and-white photos on the walls: stones, meteorite fragments? Remnants of buildings, the witnesses and remains of the architecture of a decaying memory. The real material is in front of the photos: the palpable provocation in front of the unique perspective of transformation and digital multiplication – from three-dimensional reality into the two-dimensional art, the illusion of space without depth.

And there are also the pieces of mirror formed in the red paint on the walls: unmoving, they reflect the image of the viewer for a moment, or the camera lenses. This is the bloody stability of the kinetic or programmed mirror labyrinth. An entering into the artwork, an especially ephemeral, yet real, presence.

The photosensitive imprints of belts, clip systems, and the originals of the imprints: a new phase of the cyanotype game. What are these instruments for? Are they objects of restraint and domestication or the instruments of hedonism? And how about their imprints? How far can imagination go, and if it strays far, is then the meaning assignment more efficient from the perspective of objective reality or its copy? The essential meaning of Margreiter’s series of works lies precisely in this indecision. There is no technical perfection that could overcome or eternalize the ever-changing substance of becoming.

Dorit Margreiter’s solo exhibition titled “Really!” was realized at mumok, Vienna.

Translated by Emese Czintos

Images: Hannes Böck / mumok

Ha tetszik, amit csinálunk, kérünk, szállj be a finanszírozásunkba, akár csak havi pár euróval!